There is something to the comment attributed to the British statesman Benjamin Disraeli “A man who is not a liberal at 16 has no heart; ventured, a man who is not a conservative at 60 has no head.” Aristotle makes a similar observation in his Rhetoric that youth “men have strong passions, and tend to gratify them indiscriminately. … While they love honor, they love victory still more; for youth is eager for superiority over others, and victory is one form of this.”

Taking a gentler tone, he goes on to say

They look at the good side rather than the bad, not having yet witnessed many instances of wickedness. They trust others readily, because they have not yet often been cheated. They are sanguine; nature warms their blood as though with excess of wine; and besides that, they have as yet met with few disappointments. Their lives are mainly spent not in memory but in expectation; for expectation refers to the future, memory to the past, and youth has a long future before it and a short past behind it.

This is why, he concludes, the young

...are easily cheated, owing to the sanguine disposition just mentioned. Their hot tempers and hopeful dispositions make them more courageous than older men are; the hot temper prevents fear, and the hopeful disposition creates confidence; we cannot feel fear so long as we are feeling angry, and any expectation of good makes us confident. They are shy, accepting the rules of society in which they have been trained, and not yet believing in any other standard of honor. They have exalted notions, because they have not yet been humbled by life or learnt its necessary limitations; moreover, their hopeful disposition makes them think themselves equal to great things-and that means having exalted notions. They would always rather do noble deeds than useful ones: their lives are regulated more by moral feeling than by reasoning; and whereas reasoning leads us to choose what is useful, moral goodness leads us to choose what is noble (Book 2.12).

Aristotle's observations came to mind after reading Ryan Burge's post on the political affiliation of 18-25.

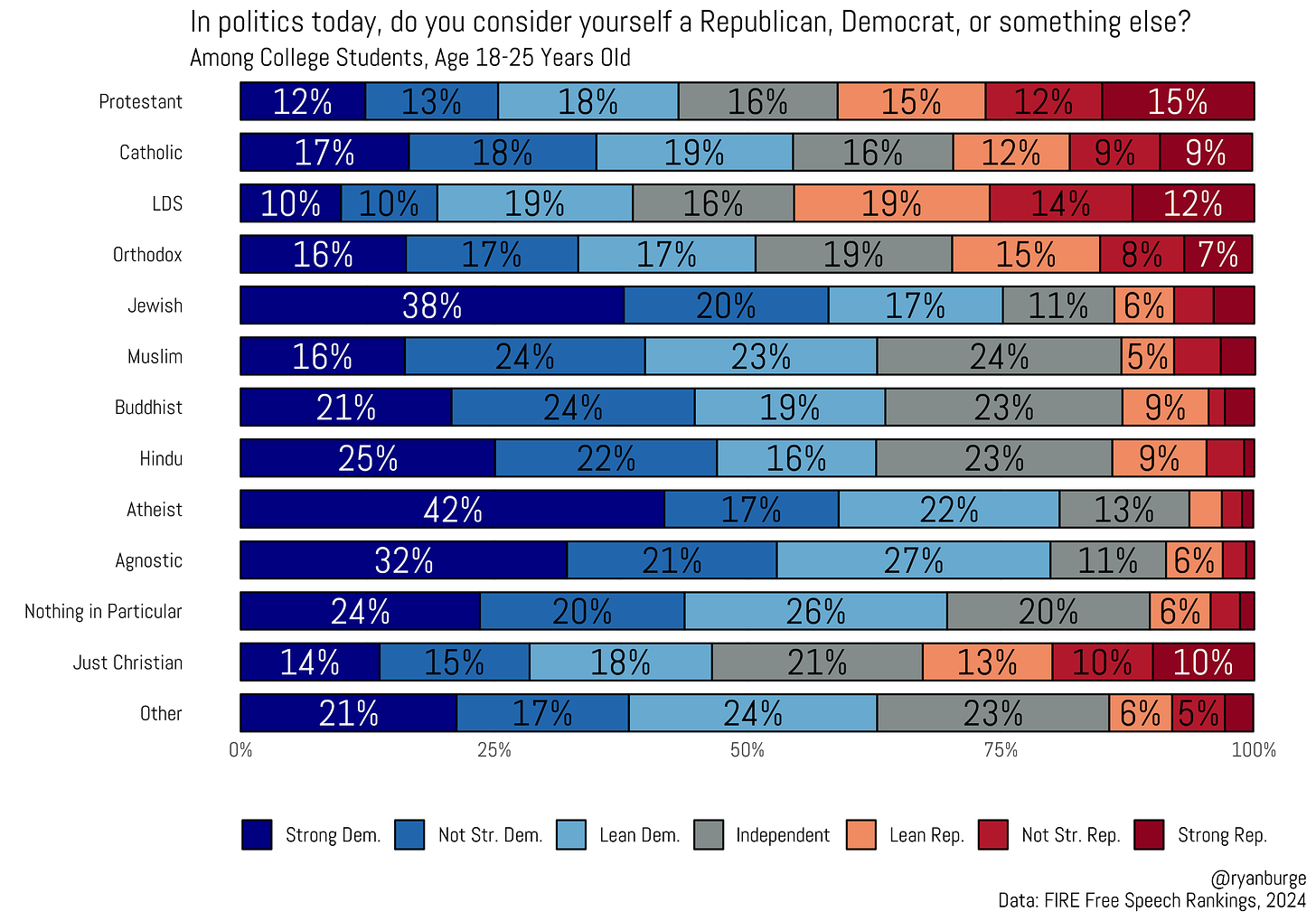

Burge begins by asking about "the political partisanship of young folks based on their religious affiliation?" Here's his chart:

Let me draw your attention to the political affiliation of Orthodox Christian young people:

Democrat: 50%

Republican: 30%

Independent: 19%

While there is no breakdown for religious practice (e.g., weekly attendance at Liturgy, daily prayer, regular confession, etc.) these figures track with my experience working with the OCF at state and private, non-sectarian research universities in Pittsburgh, PA and in Madison, WI. Orthodox young people tend to be center-left in their politics.

Put another way, the majority of young people in the Church are likely to see the Democratic Party (and liberal politics in general) as more attractive than the GOP (and conservative politics in general). Here we need to pause and return to Aristotle's observation that youth are oriented toward the future, that is they are more hopeful.

Put another way, the majority of young people in the Church are likely to see the Democratic Party (and liberal politics in general) as more attractive than the GOP (and conservative politics in general). Here we need to pause and return to Aristotle's observation that youth are oriented toward the future, that is they are more hopeful.

For many (though by no means, all) of their elders, there is a disconnect between liberal politics and policies, on the one hand, and the Gospel on the other. This, however, is likely not seen by young people in the Church. Yes, as Aristotle says, this is because they "have not yet been humbled by life or learnt its necessary limitations." However naive, their courage and hopefulness "makes them think themselves equal to great things-and that means having exalted notions. They would always rather do noble deeds than useful ones: their lives are regulated more by moral feeling than by reasoning; and whereas reasoning leads us to choose what is useful, moral goodness leads us to choose what is noble."

As a pastor and a college chaplain the challenge for me is this: How can I--how have I--channeled the courage, hopefulness, and desire for what is good and noble in the young people I serve? Retreats and mission trips are always popular of course. But resources place severe limits on who can attend.

Moreover, while Aristotle is correct when he says that as we age, we become more concerned with what is "useful" rather than what is "noble," this isn't wholly a morally good thing. Of those of us past their prime, he says that

...they have often been taken in, and often made mistakes; and life on the whole is a bad business. The result is that they are sure about nothing and under-do everything. They ‘think’, but they never ‘know’; and because of their hesitation they always add a ‘possibly’ or a ‘perhaps’, putting everything this way and nothing positively. They are cynical; that is, they tend to put the worse construction on everything.

Cynicism is characteristic of this time of life as well. And so the elderly (me)

...tend to put the worse construction on everything. Further, their experience makes them distrustful and therefore suspicious of evil. Consequently, they neither love warmly nor hate bitterly, but following the hint of Bias they love as though they will some day hate and hate as though they will some day love. They are small-minded, because they have been humbled by life: their desires are set upon nothing more exalted or unusual than what will help them to keep alive.

The elderly become stingy with money, "cowardly," "chilly" and "in fact," their fearfulness is "a form of chill." This causes them to "love life; and all the more when their last day has come, because the object of all desire is something we have not got, and also because we desire most strongly that which we need most urgently."

Looking at the data, we would be wrong to assume that Orthodox young people lean left simply because they are young. Again as Aristotle tells us, the young are moved by many things: naivety, the passions but also by virtues such as courage, hopefulness, a desire to do good and to be noble.

Maybe more importantly, and here is the challenge we face both pastorally and in articulating OST, they are often met by older voices who are no less moved by the passions than the youth--it's just that each group is moved by different passions. Or, as Aristotle has it,

Old men may feel pity, as well as young men, but not for the same reason. Young men feel it out of kindness; old men out of weakness, imagining that anything that befalls any one else might easily happen to them, which, as we saw, is a thought that excites pity. Hence they are querulous, and not disposed to jesting or laughter-the love of laughter being the very opposite of querulousness.

Discernment is foundational to our life in Christ and so to OST. The ethical challenge we face is not primarily to convince young people to become conservative (much less Republican). But neither is it to convince them to become liberals or Democrats.

But then, what are we to do?

If Aristotle is right, and I think he is, the young and the elderly live in different moral universes. We are likely not only to misunderstand each other but antagonize each other.

The response I see at most universities is to simply abandon youth to themselves. Of course, no one says this. Instead, we see people in their 30s, 40s, 50s, and older taking their lead from teenagers. Rather than guide the young, they follow them, taking their cue about the good, the true, the just, and the beautiful from those who are still unformed in these virtues. As a result, reason gives way to intuition.

The response I see at most universities is to simply abandon youth to themselves. Of course, no one says this. Instead, we see people in their 30s, 40s, 50s, and older taking their lead from teenagers. Rather than guide the young, they follow them, taking their cue about the good, the true, the just, and the beautiful from those who are still unformed in these virtues. As a result, reason gives way to intuition.

Though often well-meaning, when adults fail to guide the young, it is the latter who are hurt. The cynicism Aristotle sees in the elderly is now increasingly characteristic of the young. Adults bless youthful pieties without giving them the intellectual and practical skills they need to combine faith with effective good works.

As a result, young people experience a lifetime of failure by the time they graduate college. This I think is why we see the increase in self-censorship and growing intolerance for disagreement on college campuses. It is also, I suspect, why young people are moving away from religion in general and Christianity (including Orthodoxy) in particular. Why should young people stay with those who have abandoned them? Why respect adults who don't respect themselves but are rather eager to win the approval of their children?

Erik Erikson points out that the central task of adult development is generativity; of making sure the next generation is ready and able to meet their obligations as adults. Social and emotional stagnation results when the adult fails to successfully meet the demands of passing on the tradition to the next generation.

the failure of the Orthodox Church is not that young people are liberal, not that they are pro-choice or support LGBTQ+ rights. It is rather that adults in the Church have failed to provide young people with the moral, theological, and practical education they need to flourish and grow in holiness in these times.

Or, to put it another way, adults fail when we refuse to care whether or not young people thrive as adults in society.

Returning to Burge, the failure of the Orthodox Church is not that young people are liberal, not that they are pro-choice or support LGBTQ+ rights. It is rather that adults in the Church have failed to provide young people with the moral, theological, and practical education they need to flourish and grow in holiness in these times.

Instead, we have uncritically looked at the concerns of this time and either embraced them (thus modeling ourselves after youth) or rejected them (thus becoming the person Aristotle warns us about). What we haven't done is offer a hopeful vision for a life of "great things."

I do not comment on items posted on the internet because I don't have anything to add. However, in this case, because but this post hit's this nail right on the head, I feel compelled to say.

So, Fr. Gregory, is it fair to summarize that we (older men) need to repent to live the lives we want our children and younger, Christian brothers to live?